Optimize git commit history

There is a nice feature on docs that shows the portraits of contributors to a docs page. Despite the tiny screen space they took, the time to calculate this list can be suprisingly high.

The way how docs calculates git contributor list for an artical is simple: It first executes git log on the source file to get the commit history, then it calls some GitHub API to associate a GitHub account to the email address of each commit. If an article has the author metadata, the author appears first in the contributor list.

For repositories like azure-docs, the commit history can be huge. Today it contains 613,513 commits and is still growing rapidly each day. Unlike code repositories, documentation repositories tend to see large amounts of small commits, >50% of which are single file edits.

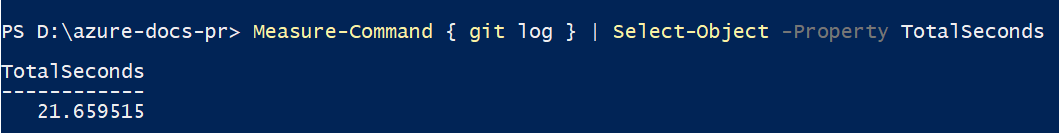

Executing git log alone on azure-docs took more than 20 seconds on my desktop:

Executing git log for some random files took somewhere from 2 seconds to 6 seconds. There are about 15,000 articles in azure-docs, even if everything run perfectly in parallel on my 8 core desktop, it still took at least 2 hours just to execute git log for every file.

This is one of the biggest performance bottleneck of the docs content pipeline. With the optimization described below, this number is now 2 minutes for a fresh build, and a couple of seconds for subsequent builds.

Read git data in process

The first step is to replace git the exe with an in process library libgit2. libgit2 comes with a NuGet package so its extreamly easy to embed to a .NET Core application. Moving to libgit2 removes the overhead of spawning extra processes, and more importantly opens up the door for further optimizations that require access to git internals.

If you are not familiar with git internals, Derrick Stolee has a series of blog posts on optimizing git for Azure DevOps. It is a bit techy but you only need to know these two sections: what makes a commit and how git stores files as a merkle tree.

How git calcualtes commit history

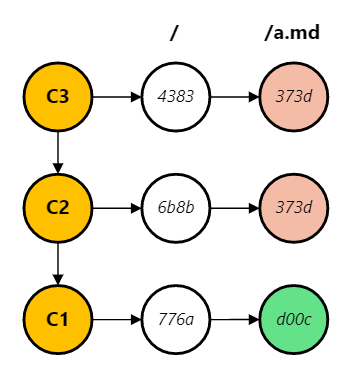

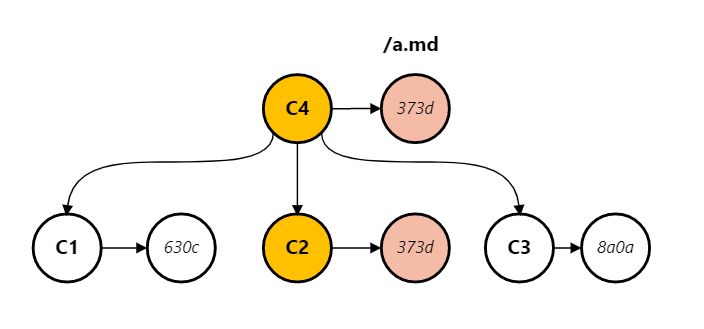

Git calculates the commit history for a file by walking the commit graph and pick the commits that changed the file. In the simpliest linear history example below, the hash for file a.md has changed from d00c in commit 1 (C1) to 373d in C2, so git log on a.md produces [C2, C1].

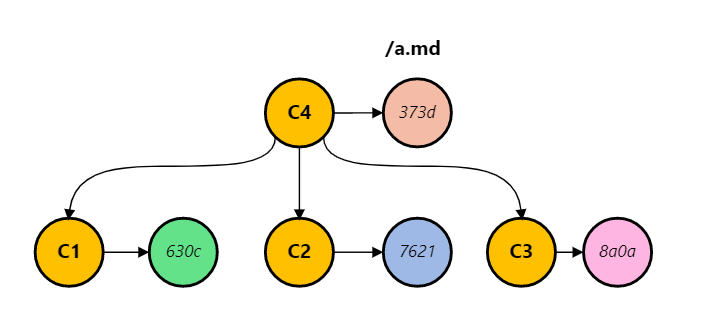

A commit can have multiple parents, when they all touched the file, git includes them all in the graph walk. In this case C1, C2, C3, C4 are all included in the git log result.

But if a parent commit does not change the file, git only includes that one commit to the walk, ignoring the rest of commits. This is the default history simplification behavior. Only C2 is included in git log in the following setup.

The commit walk graph is then sorted using a topology sort algorithm to produce a linear log of commit history.

Share git object data between files

When git calculates commit history for a file, it didn’t stop until a leaf commit. So if I create and commit a new file today, git is still searching all the older commits to see if the same file was deleted long ago. This process touches lots of objects in the git object database, old and new. Newer objects are stored in loose object format under the .git/objects/ folder and are relatively faster to read, older objects however were compressed and stored in pack files under the .git/objects/pack folder to save disk size. Reading from pack files can consume lots of CPU time on decompression.

Caching these objects in memory and sharing it across files eliminates the duplicated object database lookup and decompressions cost. This significantly improves the performance of calculating git commit history for 15,000 files.

However the memory consumption becomes high as all these git objects are loaded and stored in memory. Most of them are git object ids. git object id is a SHA-1 hash with 160 bits. They distribute sparsely across the value spectrum. In our scenario, it is possible to take the first 64 bits without seeing any hash collisions, shrinking it to long cuts the memory usage by more than a half. Using a 64 bit primitive type also gives us performance wins when used as dictionary keys. We’ll talk about how dictionary lookup speed matters below.

NOTE: chopping off bits from SHA-1 hash does have security implications. In our case the commit history is mainly for contributor list so this optimization does not harm the system.

Share git log result between files

Calculating git commit history requires a topology sort, this is usually very fast but when repeated in 15,000 files, it becomes a waste of time. If we calculate the commit history of the repository, each file can reuse the repository level commit history without having to do its own topology sort, because they share the same order. The repository level commit history is also useful for other features in docs like producing the correct updated_at time so they are needed anyway. Sharing the same sorted history this way also gives substantial performance wins.

Micro-optimize get file hash

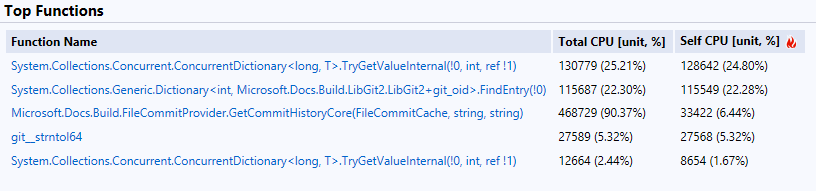

Now if you look at the Visual Studio performance profile report, most of the time is spent on dictionary lookups. That is what GetCommitHistory is supposed to do: checking whether a file has changed by looking up and comparing the blob hash code.

Represent file path using int[]

Git stores file hash code using a tree, looking up the hash code of file path a/b/c.md requires 3 dictionary lookups: a, b and c.md. Compared to a primitive type like int, using string as dictionary key involves some non-trivial overhead in GetHashCode and Equals. But how are strings mapped to ints?

The naive try is to generate a self increment id for each new string:

int s_nextStringId;

ConcurrentDictionary<string, int> s_stringId = new ConcurrentDictionary<string, int>();

int GetStringId(string value) => s_stringId.GetOrAdd(value, _ => Interlocked.Increment(ref s_nextStringId));

This eliminate the string lookup for long GetBlob(int[] filePath) method. But when getting the tree out of libgit2, it still encours allocation and a GetStringId call because we are marshalling data out of native code.

Just like the probability based optimization of shrinking SHA-1 to 64 bits, FNV1-a is used to convert from string to int. It is a widely adopted string hashing algorithm with little collision rate and it plays nicely with the new Span abstraction introduced in .NET Core. Span can represent both managed memory and native memory, that saved the allocation needed to copy a native string into a C# string.

Use a faster dictionary

DictionarySlim is an experimental dictionary from Microsoft that is a little bit faster then the stock Dictionary<TKey, TValue>. It is mostly a drop in replacement and works extremely well in our case.

Cache git log result for subsequent builds

The on disk format of git isn’t quite optimized for git log operation. Azure DevOps optimizes the git log operation by creating a dedicated commit graph file. Same idea here, commit histories for a file are saved on disk using a least recently used (LRU) algorithm. When a commit walk sees an entry in the cache, instead of continuing the walk, the cached results are used directly. Because git commit is a graph, the cached results is only usable when the graph walk stack is empty, that represents most of our cases because the commit history is pretty linear.

Same memory optimization trick is used here to only store the first 64 bits of commit hash on disk. That results in roughly 4MB disk cache size for azure-docs, which is pretty fast to sync across builds.

For subsequent builds, it usually takes just a few commit walks to see a cache entry, making the time negligible to caculate git commit history for 15,000 files in a repository with 613,513 commits.